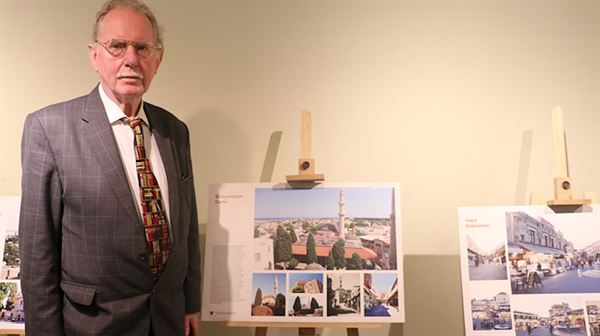

By bringing the issue to the eyes of Europe, Dutch historian Machiel Kiel made herculean efforts to save some Ottoman-era monuments in Greece from fal

By bringing the issue to the eyes of Europe, Dutch historian Machiel Kiel made herculean efforts to save some Ottoman-era monuments in Greece from falling into ruins.

The Ottoman Empire ruled the southern territories of modern-day Greece for around 400 years, and northern Greece for more than 500 years, losing them only in 1912, and leaving behind a rich legacy of historical monuments in the process.

Speaking to Anadolu Agency at a symposium held in Turkey’s Aegean Izmir province on the problems faced by the Turkish minority in Greece’s Dodecanese islands, Kiel said in the 1980s, there were two groups of intellectuals in Greece.

A professor emeritus from the Netherlands’ Utrecht University, Kiel said while one group of intellectuals viewed the Ottoman heritage in a positive light, the other did not.

The first group was smaller, while the naysayers were larger and stronger, he said.

Today, Greece’s Aegean Dodecanese islands are home to a Muslim-Turkish minority of around 6,000 people.

Kiel said there was great fear among Muslims that the 16th-century Suleymaniye Mosque on Rhodes, the largest of the Dodecanese islands, would be razed, posing a real concern.

This is because after the Ottomans lost the islands, many local Turks migrated to Anatolia, on the Turkish mainland, and some Greeks thus felt most of the mosques no longer served a purpose, so they should be knocked down, Kiel said.

“They were afraid that the same would happen to the Suleymaniye Mosque,” built by Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, he said.

Kiel, an octogenarian, said that in 1988 one of the mosque’s minarets was on the verge of collapsing, making it dangerous for passers-by, and there was a need to restore it.

But people opposed to the mosque used the damaged minaret as an excuse, arguing that even for such a historical building, if it is damaged and in danger of collapse, the whole thing should be razed.

“So I wrote two letters” in favor of restoring the mosque, he said.

“One for the governor and one for the head of the service for historical monuments.”

‘Letters went off like a bomb’

Kiel said his letters were also signed by eminent scholars from Europe, translated into Greek, and sent to Greek authorities.

“These letters had the effect of a bomb,” Kiel stressed.

He said getting the letters caused Greek authorities to think that Europe was keeping an eye on them.

“The result of these letters was that this smaller group of intellectuals, who wanted the Ottoman monuments [preserved], became the strongest, and since then they have been restoring [the Ottoman-era monuments],” he said.

A similar fate was faced by an Ottoman-era building in Komotini (Gumulcine), a city in Western Thrace, Greece, built in the 1390s.

Western Thrace is still home to a Muslim-Turkish minority of around 150,000 people.

The Gazi Evrenos Bey Imaret is a landmark monument and one of the few remaining examples of early Ottoman architecture in the Balkans. In Ottoman times, imarets served like soup kitchens for the poor or places where people could stay for some days.

Kiel said that after Greece annexed the region in the aftermath of World War I, the imaret was confiscated by the authorities. Two walls of the building were broken and it was turned into a power station, he added.

“It was incredibly dirty. They said we should have a modern power station and leave behind this dirty ruin,” Kiel said, suggesting that the building was slated for destruction.

Kiel’s article saves landmark early-Ottoman monument

But before it could be razed, in 1971 Kiel wrote a long article about the imaret which spurred its restoration.

Charalambos Bakirtzis, onetime head of historical monuments in northern Greece, told an international conference that the article had effectively saved the Gazi Evrenos Bey Imaret, according to Kiel.

“It was a very nice compliment,” he said.

Kiel said his motivation to save the Ottoman monuments was very simple.

“Why destroy beautiful things which belong to the whole world, part of the historical heritage of mankind?” he said.

When he was visiting Ottoman monuments in Greece in the 1960s, many people told him that those monuments had been left behind by “barbarians” and were no longer needed.

“Then I thought, what is a barbarian? A barbarian is someone who destroys culture,” Kiel stressed.

Thessaloniki, Greece’s second-largest city, once had around 45 mosques, but very few of them remain, and the situation is similar in Larissa, central Greece, he added.

As an architectural historian and Ottomanist, Kiel has written 17 books and 140 articles for the Turkiye Diyanet Foundation’s encyclopedia of Islam, which is one of the largest and most comprehensive encyclopedias published in Turkey.