In the ninth year of the war in Syria, the number of Syrians living outside of Syria has reached 5.6 million. Since the beginning of the war, Turkey o

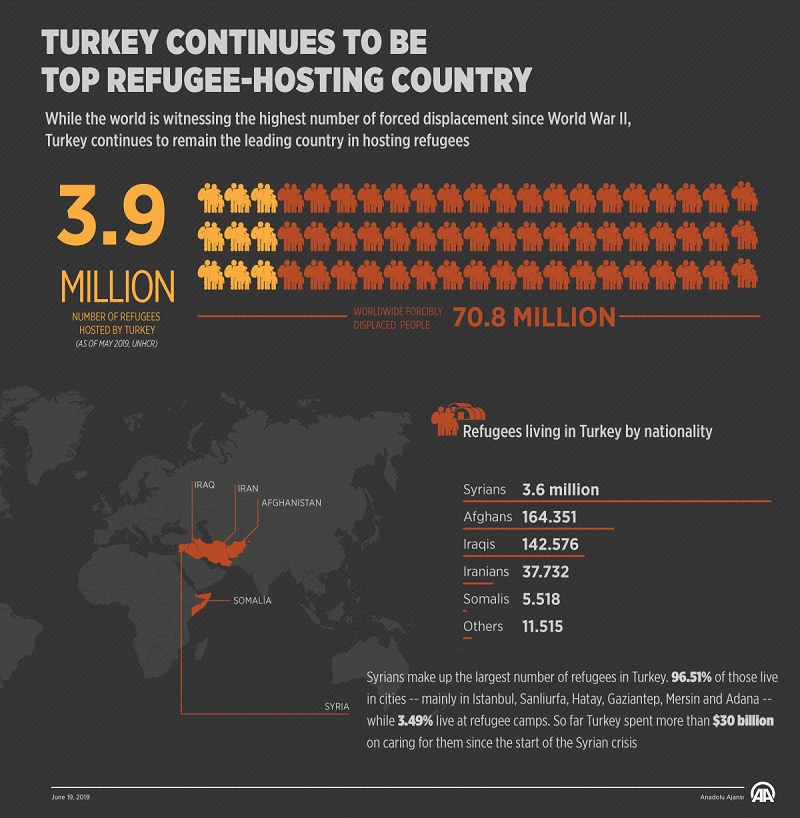

In the ninth year of the war in Syria, the number of Syrians living outside of Syria has reached 5.6 million. Since the beginning of the war, Turkey opened its doors and currently hosts 3.6 million Syrians. 64.2% of the total number living outside of Syria. Turkey has recently increased control over immigration as well as the irregular settlement of Syrians, due to increasing social disturbances, particularly in Istanbul. According to experts, although this new policy does not seem to find a decisive solution to the ongoing problem of settling and integrating Syrian refugees, it is a late but necessary decision to deal with the repercussions and reflections of one of the worst humanitarian crises of the 21st century in Turkey.

Turkey has been debating the recent government policy of increased control over refugees, particularly Syrians, living in Turkey. The government describes this new policy as an attempt to ‘prevent illegal migration’ and control the existing refugee situation. Minister of Interior Affairs, Suleyman Soylu highlighted that there will be no deportations of Syrians and other nationalities who are registered and have legal residence permits in Turkey. He added that almost 6,000 unregistered migrants in Istanbul, including 1,000 Syrians have been arrested since July 12, 2019. The government claims that Syrians who reside in any city other than their registered cities are being sent back to their registered cities. Those who are not registered in any city are being sent to refugee camps near the Syrian border, and denies the claims that Syrians are being deported back to Syria.

However, stories shared across social media and western media blame the Turkish government for a ‘crackdown’ on Syrians. Some of these stories even claim that Turkish authorities send Syrians with official permits back to war-zones, particularly the Idlib province in Syria. The problem here is twofold: the first is the ‘illegal’ residence of Syrians in Istanbul who are originally registered in another city; and second are those who have no legal registration in Turkey, i.e. who are undocumented.

In the first place, there are 547,479 Syrians in Istanbul who are registered by the Turkish government; however, the real number of Syrians in Istanbul is said to be more than one million. Similar to the reasons for internal Turkish migration from many other Turkish cities to Istanbul, a significant number of Syrians who moved to Istanbul left the cities they were originally registered in because they could not find satisfying living opportunities there, they have relatives or friends in Istanbul, or just simply because they prefer to live in Istanbul for its better living standards. This migration increased in the last three years.

As the number of Syrians increased and the slowdown of the Turkish economy became apparent after 2018, a certain discomfort emerged towards the Syrian population among locals of Istanbul. Indeed, both conventional and Turkish social media outlets together with some opposition political parties, provoked this discomfort with their rhetoric that Syrians in Istanbul were one of the reasons for this economic slowdown. Not only did the economic problems of Turkey trigger this rhetoric, but the rapid social change in Turkey during the past decade coupled with increasing nationalist right-wing sentiment, in line with global trends, added further ingredients to anti-Syrian sentiment in Turkey.

Although anyone who visits Istanbul districts with a sizeable Syrian population would find this ‘anti-Syrian’ sentiment exaggerated as the majority of the Turkish population in these districts live peacefully with their Syrian neighbors, still, one can observe certain problem between guests and hosts from time to time. It is difficult to claim that these incidents are extraordinary since the situation itself is extraordinary and indeed, there are cases of individual misconduct from both sides. The important point here is how these incidents are reported and twisted in the current age of post-truth. This does not mean that the issue of Syrian refugee settlement is not a sensitive topic. Indeed, Syrians living Turkey have become a reality and serious policies needs to be developed to accommodate this change; and if the anti-Syrian rhetoric continues to grow, the exaggerated claim of a crisis might become real.

Speaking to The New Turkey Khalid Khoja, ex-president of the Syrian National Coalition, says that from the beginning of the crisis in Syria in 2011, no one expected that it would continue for nine years and that the number of Syrian refugees in Turkey would reach more than 3.5 million. At the end of 2011, there were only 100-150 thousand Syrians in Turkey. Due to the open-door policy of Turkey, when this number reached one million, problems started to emerge and Turkey asked for help from the European Union. However, because Turkey exempted itself from the refugee agreement with the EU, they did not define Syrians as refugees, but rather accepted them as ‘visitors under temporary protection’. This status is a very unique to Turkey and it does not have any equivalence in international law. Therefore, with the exception of those staying in refugee camps, Turkey undertook the responsibility of dealing with Syrian refugees with almost no help from international institutions and countries. Those Syrians who had settled in different cities of Turkey benefited from social services, health services, and education. Indeed, these services had brought an extra cost to the Turkish State.

The huge number of Syrian refugees in Turkey did not only bring extra cost to the government but also became a security issue as well. According to Khalid Khoja, some of those who entered Turkey as refugees were not refugees; there were many Syrians who had no problem going to Damascus or Aleppo from Turkey via Beirut and could return easily. Some of these people traveling were against revolutionary groups and worked for either the Assad regime or other intelligence services; Turkey overlooked these groups of people and indeed, they became a security concern for Turkey. In other words, at some point, Turkey was not able to differentiate between refugees and this group of Shabbihas (regime spies/supporters) and is now facing the results of not dealing strictly with this situation. On the other, he adds, among those who fled to Turkey, there were many who came from the Syrian countryside and who had no means of living because of the war; these people also fled to Turkey just to earn a living.

Therefore, Khoja says, this policy of strict control over Syrian refugees is necessary and is indeed a delayed one. He says, this policy had to be applied since the beginning of the crisis. When Syrians arrived Turkey, there had to be a security control during the registration process. This control, he argues, could had been done together with officially accepted opposition groups like the Syrian National Council or the Syrian National Coalition, in order to find out who were refugees, who belonged to opposition groups or worked for the Assad regime; but this was not preferred by the Turkish government. The new policy of strict control of the Turkish government arrived as a necessary outcome of this process according to Khoja.

Khoja further argues that the timing of this strict control is also related to the rhetoric of Turkey’s opposition parties as well as the general public view towards Syrians. According to a public survey done by Bilgi University in 2018, more than 80% of Turks, both the supporters of current administration and opposition parties, believes that Syrian refugees should return to Syria. In another survey done in 2019, couple of months ago, by Kadir Has University, Khoja adds, only 10% of the supporters of AK Party in the big cities think that Syrians should stay in Turkey, and almost 60% of the AK Party supporters think that Syrian refugees should go back to Syria. Khoja says that these surveys indicate that the Syrian issue has become a troubling issue for the Turkish society.

Khoja notes that some people explain this new policy as being a response to the results of recent local elections in which the current government lost both Istanbul and Ankara municipalities; however, he does not see this argument as accurate, because the issue became significant before the elections, and the government decided to apply this policy before the elections, only introducing it afterwards.

According to Khoja, Syrians who are registered to live and work in one city and moved to another city present a problem for the government, because it is difficult to track these people, but what is inconvenient here is to deport Syrians back to war zones. He confirms social media reports that among those who were sent back to the war zones in Syria, there are Syrians who are registered with identity cards, those who are not-registered and even those who have identity cards and legal permits to work. He argues that the reason for this illegal deportations is not that they are the orders of the government but rather the arbitrary decisions of the officials on the ground who did not follow the instructions of the ministry during the process.

Khoja says, officials of the border administration at Idlib told him that 1,000 Syrians were deported to Idlib by the end of July, and among them there are those who have identity-cards and registration in Turkey. However, he says, the minister of internal affairs recently stated that there will be no more deportations of Syrians to war-zones, therefore this is a positive step towards preventing arbitrary decisions and will lower tension among Syrians.

Khoja says he supports the idea that the government should work together with NGOs focusing on Syrian refugees in order to find the best solutions to the ongoing crisis. If the application of government orders is left only to officials on the ground, there might be similar arbitrary decisions in the future. He says, the important issue is the improper treatment towards Syrians, but one should not forget that the issue has been manipulated by some Syrians who are working for the regime in Syria. Therefore, it is quite important for the government to be in coordination with the NGOs. This point is also important, he adds, because both the Turkish government and society has sacrificed for the Syrians since the beginning of the crisis, and no other country in the world did what Turkey has done for the Syrians. These sacrifices should not be shadowed by the improper application of this new policy and the negative campaign developing around it.

Speaking to The New Turkey, Müberra Nur Emin, researcher at SETA Foundation and the author of ‘The Education of Syrian Children in Turkey published in 2019, says that the Syrian issue is not a new one; the crisis has been going on for the past nine years and every year both the number of Syrians and the problems around this flow are increasing, making the issue more complex. She adds that the number of Syrians in Turkey is almost reaching four million and the intensity of Syrians in certain districts of Istanbul, or in the border cities like Hatay, Gaziantep, Kilis, Urfa, Maras, have affected both the dynamics of the society and complicated the administration in these areas. Therefore, it is very normal and necessary to see the intervention of the government at this point, which may even be considered a late decision, because each day brings a new dimension to the issue and results in changing demographics of certain areas.

According to Emin, the recent government policy should be analyzed in this perspective. She argues that if there will be an integration process this needs to be twofold: both for the hosts and visitors. Indeed, she adds, at the beginning of the Syrian crisis the government developed policies with the assumption of short term residency of Syrians in Turkey. However, the unexpected duration of the war as well as the military involvement of foreign actors have caused a deadlock in the war; and the government has faced big challenges that delayed the development of a long term strategy. At this point, she says, the government realized the necessity of a long-term strategy and this recent government policy is its initial steps.

Another aspect of the issue debated by some experts is related the manipulation of image of Syrians for political gains. Both major opposition political parties and certain media outlets have been using rhetoric which is politically incorrect and causing a negative image of Syrians to the broader society. With the global trend of increasing nationalist sentiment, certain Turks see the arrival of Syrians as a threat to Turkish society and the economy. Even though the number of these people are not a majority among the Turkish population, the voice of this group is heard louder within society and is getting more supporters each day. For example, distorted information monthly stipends, their education is free, they do not pay taxes, among other claims is spread with conventional and social media and Turkish people have been developing negative opinions about Syrians as a result of this fake news.

Some experts even argue that the sensitivity of the issue could be manipulated by foreign intelligence services to create an enmity between the hosts and visitors in order to put the government in a difficult situation which is involved politically in the Syrian crises. This is also one of the arguments of the anti-Syrian bloc in Turkey who argue that the placement of Syrians in Turkey aims to damage Turkish society and create a chaotic environment.

Regarding the claims of the return of Syrians to the war zones in Syria, Emin argues that this is not legally possible with Syrians who are under the ‘temporary protection’ status; however, she adds, there might be individual cases where this has occurred with those who do not have this status. She also says that the authorities need to deal with ‘fake’ news quickly and prevent spread of misinformation s and conduct a strategic communication to inform the public.

Emin also agrees with Khoja and highlights the importance of getting the support of NGOs working in the field. She says, since the beginning of Syrian migration to Turkey, there have been serious NGOs working on the issue, providing education, employment, shelter, food, etc. In this regard, she adds, it is important to get the support of NGOs as the mediators between government and society, in order to have a healthy communication both with the locals and visitors, and to administer the relations between them.

According to Emin the deadline of the government for Syrians to move to the cities they are registered to (August 20, 2019), is short notice for those who have started a life in a different city, since finding a place to live and work in a new city would not be easy in this short period of time, and even harder for those with kids studying at schools. Therefore, this deadline needs to be modified, if not for all, then for those with special conditions. Another important aspect, she adds, is that those who are living in Istanbul mostly registered in cities in the south-east of Turkey which are highly populated with Syrians and there is almost no more space in these regions. Therefore, a serious long-term settlement policy for Syrians is needed urgently.

At the beginning of August, 2019, Istanbul governorate said in a public statement that 2,630 Syrians in Istanbul who are not registered in any city were dispatched to temporary protection centers to the cities determined by the ministry. In a press conference in Ankara, the next day, August 2, 2019, Sulayman Soylu said a total number of 92, 280 people (47 thousand adults, 42,280 under the age of 18) were given Turkish citizenship.

Müberra Nur Emin confirming Khoja’s earlier comments highlights the fact that both Turkish society and the Turkish government have done much for Syrians in the last eight years since the beginning of the crisis and this new policy towards Syrian refugees should not overshadow this sacrifice.

COMMENTS